Everyone wants to be data driven, but no one knows what it means, or how to achieve it

Many leaders say their organisations are struggling

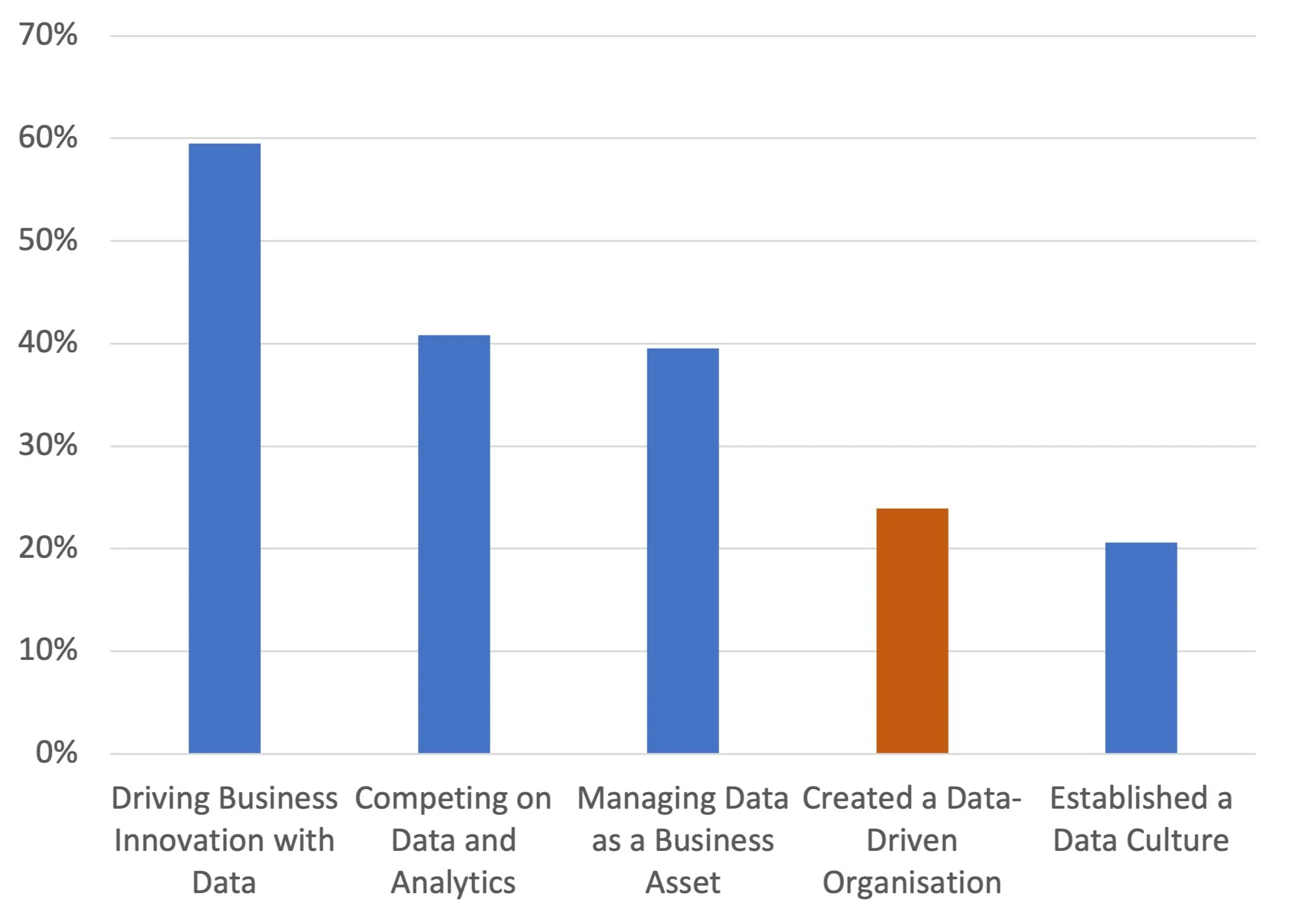

Fewer than a quarter of data executives in leadership positions say their organisation has become data driven.

Some organisations make heavily data-driven decisions because making wrong decisions is very expensive, either because they make a lot of decisions, e.g. banks approving loans, any other organisation approving credit or because the decisions are about very large, non-reversible investments, e.g. oil companies deciding where to drill, FMCG companies deciding what products to make, car companies deciding what cars to make.

Other organisations use data to help them make decisions because of regulatory intervention, e.g. pharmaceutical companies trialling drugs.

Governments use data to help them make decisions about how to spend public money, e.g. in the UK the Public Accounts Committee (a group of MPs from the House of Commons) can request the National Audit Office (an independent public body) investigate anything the government does and check to what extent the public has got good value from the spending. Ministers and senior officials have to explain in public how decisions were taken and how evidence was used to support the decision.

With increasing digitalisation of production facilities, and the workplace in general, more and more data has become available with which to make decisions. The growth in popularity of Six Sigma, Lean and other process improvement methods over the last 20 years has drawn more attention to data analysis where there had not been much before. Now even small start-ups are able to finely tune their business based on tight feedback loops from their website and other systems generating data using off-the-shelf products.

No one is debating that there is a lot of data available, at very low cost, to every organisation.

The challenge is how to get the best value out of it.

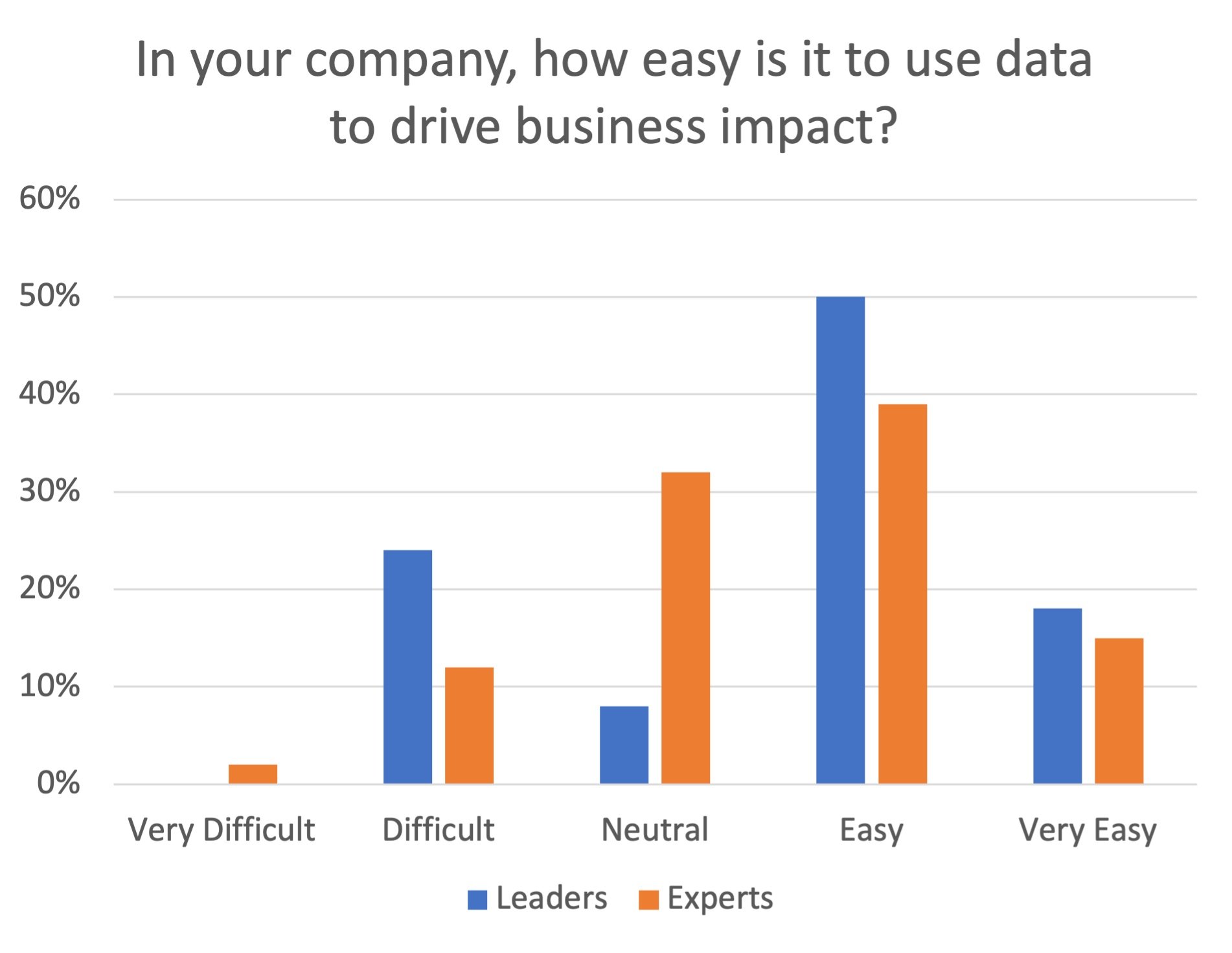

Over a third of Data Leaders and experts think it is not easy to drive business impact with data in their organisation

And Data Experts have an even more pessimistic view than Data Leaders.

Leaders and experts from across the world are all busy proposing solutions to the problem of how to become more data-driven. Your LinkedIn feed is probably full of points of view and articles that are trying to help.

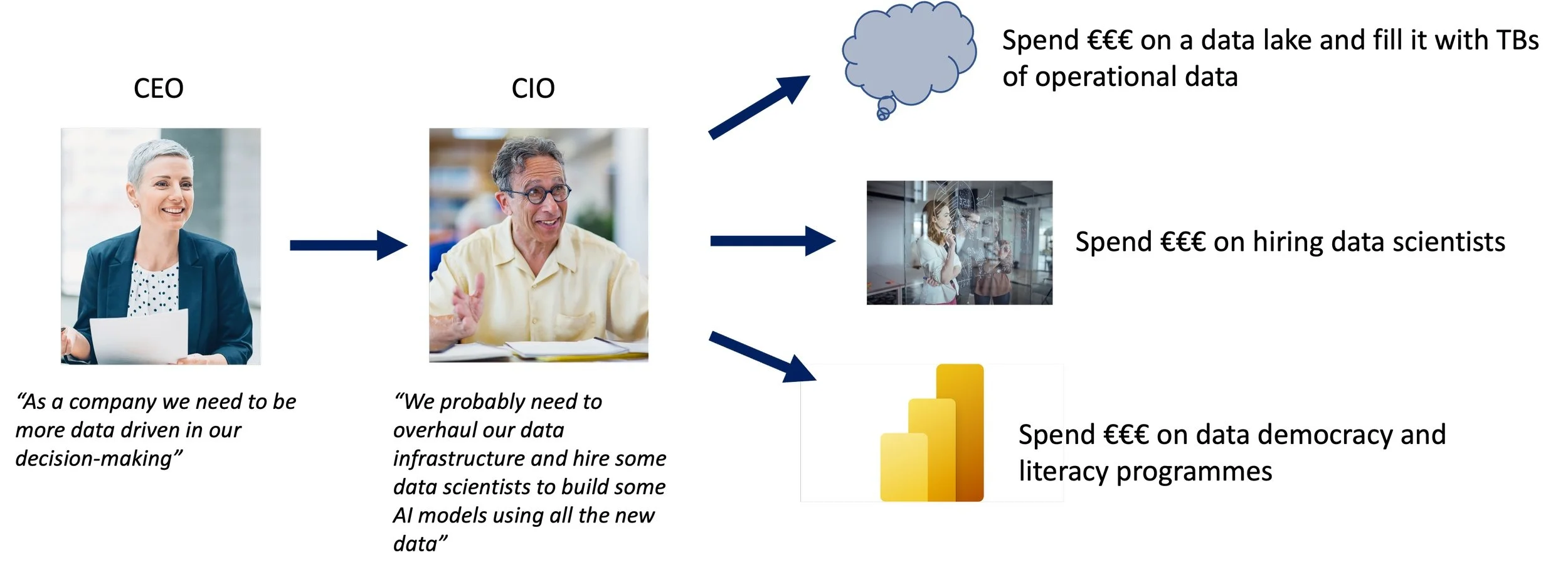

Part of the problem is that becoming more data driven is often seen as a responsibility of the CIO or CTO. There are some solutions which can help but because the issue is bigger than the remit of a CIO or CTO, they cannot solve the problem on their own.

The most common solution

tech / data organisation - "bringing all of our operational, financial, web and CRM data together in a single place will definitely give a small bump in operating margin, right?"

With the growing volumes of data has come an industry supporting its organisation. From data ski lodges to streaming data from your CEO's brainwaves, there are an infinite range of things you can do to better capture and organise your data.

However technology on its own will not make you more data driven in your decision-making. Having incredible volumes of data sat in AWS and growing by zetabytes every second does not provide anyone in the company with more evidence about what is the best choice to make. It does not help a sales manager decide where to focus their time. It does not help a procurement team reduce their supply chain risk.

Static data does not answer your questions.

data scientists (and how they are organised) - "hiring more nerds will increase operating margin by at least 3%, right?"

Since Big Data and Machine Learning became popular earnings call bingo topics in the early 2010s, hiring STEM Phds to build random boosted binomial tree networks has been become a common strategy to try and demonstrate value from data.

Until recently, some of the most valuable applications of machine learning were out of reach because regulations stipulated that only older, more transparent approaches were allowed, e.g. banks still choose to use binomial logit models for credit approvals because they are very easy to audit compared to other more sophisticated machine learning frameworks.

Nevertheless, predictive analytics has become an important topic in many industries: predicting failure rates in physical systems, predicting which customers are likely to leave.

While there are many valuable applications of predictive analytics, the excitement around it has also crowded out more fundamental, less exciting analysis, like understanding variation in an outcome and what causes it.

The tendency of data scientists to sit under the CTO in many organisations also means that their priorities are aligned with more technological objectives than business-related: "I've just invested a lot of money in system x, now I'd better get some data scientists to work on the data to demonstrate system x is good value".

This ends up looking at things backwards - the most valuable things a data scientist can do for your organisation is not necessarily a subtask on the to do list of the CTO. At the very least, the most important conversations for a data scientist to be part of are not with data engineers and developers, but with people in other parts of the business who can see where impact is needed.

data democratisation - "giving people access to a hundred different dashboards that they can slice and dice will increase operating margin by at least 15%, right?"

74%

Proportion of employees reporting feeling overwhelmed or unhappy when working with data

Source: Accenture/Qlik: The Human Impact of Data Literacy

A more recent theme in discussions about improving decision-making is data democratisation. This is the idea that many employees are constrained in their effectiveness because they do not have enough information at their fingertips, and the solution is to give them more control over what data they can access and how they can access it: interactive dashboards with lots of filters, connected to live data, rather than static pdfs or excel tables. Like the other proposed solutions, this one is not an inherently bad idea. However, it assumes that people have a good understanding of the problem they are trying to solve, and its strategic importance. It also assumes people have the skills and knowledge to navigate the data available to them and use it appropriately to answer their question. This is a very strong assumption.

data literacy - "teaching everyone about all our data sources and why pie charts are evil will surely double our operating margin, right?"

Data literacy is the solution to the issue with data democratisation of people saying they are overwhelmed by the data available to them. It aims to give them the skills to handle it and process it into something they can use to make a decision. Many of the features of data literacy training programmes are similar to what is taught in Lean and Six Sigma, although with less of a process improvement focus. This kind of training is clearly not a waste of money, but it doesn't necessarily address the problem of business performance because it doesn't teach people about the kind of questions they should be asking in the first place. This is not something you can learn from Jordan Morrow, nor is it something you can buy from Udemy.

None of these solutions are bad, but they also won't bring your organisation closer to data driven decision-making. Why?

Firstly, these solutions are nugatory and only address one part of a what is a complex and systemic issue. None of the solutions address how data is used in decision-making. None of them address the question of what data, tools, models and graphs are best suited to addressing a particular kind of decision in your organisation.

Secondly, they are non-strategic. In particular, tech/data organisation, democratisation and data literacy programmes tend to take a scatter-gun approach, focussing on high volume. Data-driven decision making is partly a cultural challenge and as with other cultural challenges, change needs to begin at the top. Why focus data literacy programmes on more junior employees, when the board and senior executives are the ones making the most expensive decisions?

Thirdly, the solutions are not value focussed. None of them start with the business' goals in mind. Without this, money and time are wasted on endeavours that may deliver some value, but are not necessarily delivering value to a strategic goal.